Nur's stepsisters

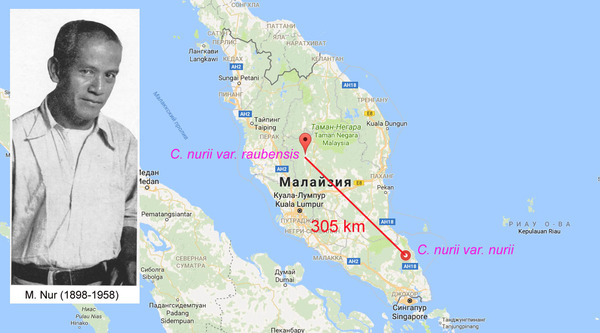

Oh those sisters! Even being relatives, they usually have a huge number of differences, and this applies not only to their appearance, but also to the internal content, or – should I say? - character. Let alone the sisters (Figure 1), whom Mother Nature separated in space for several hundred kilometers over several million years...

Figure 1. Map of the Malay Peninsula with locations of two varieties of Cryptocoryne nurii. The insert shows a photograph of Mohamed Nur.

The first of them languished in the shadow of a tropical forest in the waters of the Telepah River (Sungai Telepah), that flows from north to south northwest of the Malaysian administrative center of Kota Tinggi (Figure 2). The thirty-year-old collector Mohamed Nur (Mohamed Nur bin Mohamed Ghose) was not a newbie in his field: he had begun collecting tropical plants for the world's leading botanical gardens at the age of 15. Perhaps it was his rich experience that helped him not to miss such a miniature aquatic inhabitant, which 7 years later, in 1935, was named after him - Cryptocoryne nurii.

Figure 2. Habitat of Cryptocoryne nurii var. nurii. Mersing, Johor, Malaysia.

It is worth noting that Mohamed’s discovery was extremely secretive and “feather-bedded”. Our attempts to track down Cryptocoryne nurii in July 2017 pretty much frayed our nerves. Unlike the 90 old year events, we decided to bypass the Gunung Panti forest not from the left, but from the right side. Moreover, the Johor Baru-Kuantan highway made it possible to do this without any difficulties. A little before reaching the port city of Mersing, we turned left and went deeper into the peninsula for a couple of kilometers. The car was left behind on the road; the path led us through a completely gloomy forest. There was hardly a single blade of grass in the lower storey, and the shape of tree roots in the dark light resembled snakes. The whole soil was digged over by tapirs (Tapirus indicus). I confess that even in domestic forests, such tricks of wild boars create a slight chillness in my chest, to say nothing of a completely unfamiliar Malaysian foreign land. Having reached a small river 3-4 meters wide, we wandered along the channel for a long time, but there were no signs of Cryptocoryne at all. The continuous buzzing of cicadas, combined with the gloomy atmosphere, psyched us out, causing only one desire - to return as soon as possible. However, the final attempt to walk a little further along the channel was crowned with success. A group of dozen small bushes of Cryptocoryne nurii rooted on a sandbar (Figure 3). Small brown leaves fuzzed with the background tones of the area, leaving its modest inhabitant almost invisible. A little further upstream, among the young shoots of pandanus (Pandanus sp.), we managed to find several green emerged bushes, which also did not differ in size (Figure 4). A few minutes later, my wife found a leech stuck on her heel, and we did succumb to the new wave of panic and left the biotope.

Figure 3. Several bushes of Cryptocoryne nurii var. nurii was found under water on the sandbar of a small forest river.

Figure 4. Cryptocoryne nurii var. nurii: emersed culture (on the left ) and submersed plants (on the right). In the latter case, it is likely that the plant occasionally comes out of the water, depending on the amount of rainfall. Note the variety of colors of the leaves of the plant, depending on the growing conditions.

This is how we met Nur's first sister, who is now usually recorded as the variety Cryptocoryne nurii var. nurii. And she was “spoiled” by the water, which is super soft and sour in the rivers of the state of Johor. Our measurements: pH = 5.6, TDS = 8 ppm. For this reason, the plant could not be kept in aquariums for a long time. We also were not able to keep this Cryptocoryne alive in culture, therefore, this miniature beauty with an amazing dashed leaf color is still a “challenge” for us.

If you travel 300 km north of the place of previous events to the state of Pahang, you will find yourself in an opposite world. Among Cryptocoryne lovers, this place is called the “Kingdom of Affinis” after the Latin name of Cryptocoryne affinis. Exactly there we found Nur's second sister, Cryptocoryne nurii var. raubensis (Figures 5-7). Raub is the name of a small town near which several populations of this plant are located. With the exception of the famous Taman Negara National Park, there are practically no virgin rainforests left in this region. The harmonious rows of oil palms (Elaeis guineensis) underprop the horizon. However, such rearrangements in no way affected the Cryptocorynes in local rivers. Having changed the shadow of the rainforest for sunny plantations, the aquatic plants have remained within the same boundaries of their biotopes.

Figure 5. The river Sungai Tealng. The stone framing of the banks is due to the presence of a road bridge over the river in this place. Cryptocoryne nurii var. raubensis is completely submerged. The current is strong.

Figure 6. Cryptocoryne nurii var. raubensis. State of Pahang, Malaysia.

Figure 7. Epipremnum amplissimum is one of the few semi-aquatic plants in this region. It can be successfully cultivated both in an aquarium and as a houseplant.

After we had visited several rivers with Cryptocoryne affinis, we went down to the next object of study. The bottom of a small stream, called Sungai Tealng, was almost entirely covered with small Cryptocoryne plants, resembling C. affinis in color, but significantly inferior to it in leaf size. There were no inflorescences, so we were not sure that we had found Nur’s Cryptocoryne. We had to wait for several months, until the appearance of those plants in culture dispelled our doubts. Simultaneous cultivation of our find with Cryptocoryne affinis was carried out in the greenhouse for aquatic plants at the Botanical Garden of the Lomonosov Moscow State University, where the leaves of the emerged Cryptocoryne nurii turned out to be completely smooth, unlike its neighbor (Figures 8 and 9). The proximity of the biotopes of these plants is so big that there are many examples described in the literature when both Cryptocorynes had been found in the same stream or river.

Figure 8. Cryptocoryne nurii var. raubensis (on the left) and Cryptocoryne affinis (on the right) in the Botanical Garden of the Lomonosov Moscow State University. Note the smooth leaves for C. nurii and the corrugated ones for C. affinis.

Figure 9. Greenhouse of aquatic tropical plants of the Botanical Garden of the Lomonosov Moscow State University.

Unlike the first sister, the second Nur’s Cryptocoryne settled on calcareous rocks, which greatly influenced the water parameters in this region. At the place of our discovery, the water had the following parameters: pH = 7.24, TDS = 27 ppm, and illumination at 16:30 local time was 2000-6000 lux. The recent successes of domestic aquarists in growing Cryptocoryne nurii are associated exactly with this plant, which successfully reproduces and blooms in aquariums with ordinary Moscow water.

Feeling satisfied with the fact that our observations of natural biotopes contribute to a better understanding of Cryptocorynes’ world, I have to put an end to this story. But this should not upset you, in the future we will have many more exciting ones...